AMBER WAVES OF GRAIN

Memorial Day weekend is the opening to summer that Labor Day closes.

Years ago, I wrote a meditation on the fall that contained some version of the line, “If Fall had an archway, this would be it.” And a similar line would work here, that Summer officially started this past weekend.

All around us, the community sprung into motion, as if the spring season had pent up some untapped reserve of kinetic force. My friends filled their Facebook and Instagram and Twitter feeds with reports and pictures of movement, point A to point B, fun all along the way, pictures of barbecues and lake outings and beaches and camping and Nascar races and parties. The pumps are running at all of the swimming pools, and thousands (or millions!) of us braved the temperatures, this spring more fitting in October than May, and splashed around in glory.

As for me, I left work Friday around lunch and picked up my golf clubs, inspired by a friend who was doing the same thing, and drove straight to the little county course near our house. I bought a pair of hot dogs, and a cold beer, and a bottle of water, and a bucket of range balls, and a round of nine holes. It had been about two years since I’d been out on a golf course. Better to ease into it.

With the brilliant sun at my back, and a steady breeze on the driving range, I launched round after round, lofting each shot with such a decent swing that I looked at my hands, stunned, questioning how on earth my arms and fingers and shoulders could remember how to work a golf club after all this time. I stepped onto the first tee box, a casual dogleg left that challenges my oft-fading tee shots, and fired a drawing missile that laid up no further than a hundred yards from the green. I made five pars in nine holes on my first outing in two years. I may never play golf again.

I came home that afternoon and celebrated with Kelly and Julia and Thomas, and we ate a good supper out at a good Italian restaurant and went over to the school where Kelly works and played on the playground as the evening settled and cast long shadows over the fresh grass.

Julia and I ran across a field together, over to where the old baseball field sits, the same field where I played little league baseball, where behind the backstop, next to the woods, I’d warm up with my pitcher (I was the catcher), and we’d play the dominant East team, each of us impressed with what was then a terrific ballpark, with dugouts that were actually beneath the ground level and had roofs and real benches, not the aluminum ones. It was a real ballpark to kids like us.

Now it sits, grass invading infield past second base and aiming to take over the pitchers mound. Julia walked over to the dugouts, climbing around, and I felt the cold chill of mortality on my neck, the feeling any warm-blooded parent gets when he takes his daughter to a place he knew as a child, frozen by the perspective of it all. It made sense why some people leave home and never come back, why they raise their families in new jungles, too astounded would they be to return to their own childhood, too overwhelmed by the decades between them and the new blood, the winnowed years between now and the end, the setting sun, the waning.

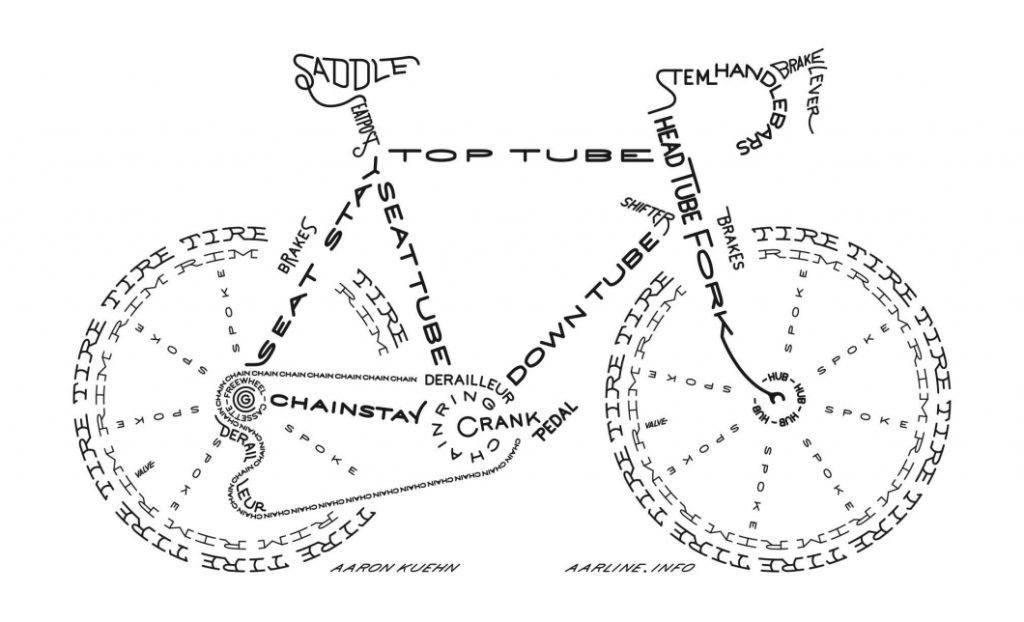

Saturday I pumped up the tires in our bicycles, each measure of air into them a small accomplishment. We have hybrid bikes now, the kind with skinnier (but not too thin) tires that ought to be rock solid. I rub away the dust on each chassis, wipe away a winter’s worth of cobwebs from the basement storage, and spray on new lubricant for the gears and derailleurs. Beyond this basic maintenance, not much else, except to check the bolts on the child seat on the rear of Kelly’s bicycle and pump up the tires on the pull-behind trailer that we put Thomas in. Taylor barks as I work, an open admission of frustration that I’ve figured out how to pull around two children on our bikes, but I’ve never found a way to pull her, the dog.

We load up and take off down the street, the fading barking behind us, off to the green way, under the canopy of new leaves that spits us out at the soccer park. How many times have we pedaled out this far, and every time the west-facing approach still leaves my lungs filled with something big.

About a mile or so up, two young African American boys appear from the cloak of the woods, as if they’ve conquered invisibility, and immediately we hear, “Hey, I know you! You’re our music teacher.” And Kelly smiles and recognizes them. They are on a pair of matching bikes, and they are brothers.

I recognize their names. Years ago, I had to drop off something at the school on my way to work, and Kelly introduced me to the class that happened to be there at the time, calling me Mr. Hogan. I was on my way to a meeting, so I had a coat and tie on. One of the brothers was in the class. “He yo’ husband?” he asked Kel after I’d left. And then:

“Do he beat you?”

I could fill this screen with the imagined horrors of growing up in a home in which domestic violence fills the vacuum left behind when stability disappears. Instead, though, I want to paint the picture of these two boys, each eager to show off on their bikes for their teacher, and how we all rode together, two bandit fifth graders, a pair of lily-white babies, and Kelly, and me. They are twins, their names rhyme, but one is stuffed with dare, the other burdened with responsibility, and they are different.

The risk-taker can zoom his bike down a hill and stand with one foot on the bike seat and swing the other leg out behind him, dancing with his machine like an Olympic ice skater. The other is satisfied with pedaling as hard as the fixed-gear bike will go, racing past our slow-motion caravan, his pearly smile more than enough.

One of the boys, the one who asked so earnestly if I beat my wife, has a rap sheet and a parole officer and a habit of smoking cigarettes. There in the woods, though, upon the sunlight dappled trail, there in the evening of the weekend in which we all emerge and plant our flags for God and summer and country, there with us, the boy was just a boy, a child eager to hear his teacher’s approval, a child who didn’t want to hear his brother’s calls that they should go home, that it’ll be dark soon.

We are racing each other, except Kelly and I aren’t really racing. In the pit of both our stomachs, unspoken, is a fear that these boys are really lost, that they somehow just stumbled upon us on the trail, and that they’ll follow us back to our house, and I’ll have to load their tiny bicycles into the minivan, and we’ll drive into a part of town that I avoid, the boys in the back seat because it’s the law and I have to observe it, the ridiculousness of it and all. I won’t keep painting this picture.

As we unspooled our own kinetic motion, the ground flying underneath, I knew that this was right, this moment of simplicity, two adults who are making it up as we go, our two children, and two more who joined us for a part of the ride.

How else would we open up the door to summer?

Leave a Reply