It is quite easy to forget that on the morning of September 11th, very few people thought that the twin towers would actually fall, that the audacious spires of steel and glass and concrete would betray the rescuers climbing heavenward inside their cramped stairwells, and give out, and vanish in enormous clouds of dust. Instead, we imagined the fires would be extinguished, that the buildings would be fixed, and our lives as we had known them until that point would simply continue.

We were wrong.

“Oh my God.”

You can go back and find full broadcast episodes of the major network morning shows from the morning of September 11th and see for yourself how naïve we all were. Five minutes after the first plane struck the north tower, Good Morning America‘s Diane Sawyer returned from an otherwise mundane commercial break to carefully attempt to describe what becomes the first of many horrific and unprecedented television images from that Tuesday.

The slow, deliberate pace with which Sawyer describes the scene–the tower, captured from a news chopper, a black scar high across its upper reaches, fatally engulfed–exemplifies the relative innocence we all woke up with that morning.

“We want to tell you what we know as we know it,” Sawyer says, a look of concern on her face. “One report said–and we can’t confirm any of this–is that a plane may have hit one of the two towers.”

Three minutes later, Don Dahler was on the telephone, as correspondents of the day were often connected, reporting a few blocks away from the World Trade Center. His voice is agitated; he knows something horrible has happened, but he’s not sure what. “I don’t want to cause any undue speculation” he says, twice, reporting what he heard sounded like a jet or a missile hitting the building. Charlie Gibson chimes in: “We have to underline that we are dealing purely in the realm of speculation.”

As the digital clock superimposed in the lower right corner of the news report clicks from 9:02 to 9:03, speculation was quickly put to rest.

Dahler, on the phone, was noting how little effort there was to try to control the fire in the north tower when the second plane struck. “Oh my God,” he said, a phrase repeated quietly by Sawyer: “Oh my God, my God, oh no.”

Gibson jumps in with the firm voice of a veteran newscaster, to confirm in words what we had all just witnessed. “This looks like some sort of concerted effort to attack the World Trade Center.”

This now being the biggest news story of the 21st century, Peter Jennings soon took over the network’s helm, jumping from one update to another. The fires were raging out of control. Tall buildings are being evacuated across the country. The White House is being evacuated. There may have been a car bomb at the State Department. We understand there are other planes that may be hijacked. In Washington, D.C., we’re getting reports of smoke.

Later, the attention had turned to the Pentagon, the screen split into two boxes showing a zoomed-in shot of the south tower and the scene in Washington. You can hear a correspondent talking to Jennings about the FBI and the CIA, sounding smart and informed and in control, when unbeknownst to the hosts, the walls of the south tower crumbled, and the entire, mighty colossus plummeted to the ground.

Eventually, the on-air talent noticed, and the producer cuts back to New York. “Let’s go to the Trade towers again,” Jennings directs, “because we now have. . .a. . .what do we have? We don’t….”

Jennings doesn’t know. “It may be that something fell off the building,” he guesses in his smooth, baritone voice, as a ghastly plume of concrete dust blooms seventy stories tall on the wide angle shot. “We don’t know to be perfectly honest.”

Those of us watching knew. Don Dahler knew. In his rush to get him on the air, Jennings calls him Stan.

“The second building that was hit by the plane has just completely collapsed,” Dahler reports. “The entire building has just collapsed. It is not there anymore.” In the background, someone at the news studio repeats the common refrain of the morning as the producers queue up a replay of the devastation. My God.

Incredibly, Jennings doesn’t seem to have been paying attention. He’s missed the instant replay. We hear someone say something to Jennings, perhaps handing him a printout, and Jennings, noting that Dahler’s stopped talking, thanks him for his report, calling him Dan this time. He seems only to have heard the very end. “The whole side has collapsed?” Jennings asks on the air.

“The whole building has collapsed,” Dahler repeats.

“The whole building has collapsed?” Jennings asks, and for the first time, you can hear incredulity betray the professional tone with which he has thus far narrated the morning. At some point he sees with his own eyes what’s occurred, and along with the rest of us, he quietly begins to accept the fate that has just befallen thousands of people in lower Manhattan. “We are talking about massive casualties, and we have…” he trails off, before letting out a sigh of disbelief and falling silent.

The millions of us watching all of this on television likely fell silent with Jennings*. We never thought the towers would fall, because never in the history of skyscrapers had this happened. Then again, never in history had we ever turned on the television to see someone fly a commercial passenger jet into one.

Considering this, these television broadcasts were sanguine–from ABC’s Jennings, to NBC’s Tom Brokaw, to the desk reporters at CNN and elsewhere, the anchors deliberately, calmly, professionally gave us the news. The images we were shown were mostly taken from afar. Even the second plane’s impact was filmed from a distance where it looked almost abstract: a dark plane, a spot at first on the horizon, recorded at a distance that jilted crushing reality.

The clear and murderous violence of it all would come later, as vantage points surrounding New York City sent in what they had captured. Professional camera crews responding to the crisis captured thousands of people running in terror as the second plane hit. Richard Drew trained his telephoto lens toward the north tower’s highest purchases, snapping frames as a man jumped to his death from Windows on the World.

*Note: In fairness to Peter Jennings, who was my favorite news anchor when I was younger, it was incredibly hard to have a sense of what was happening from a television studio. NBC’s coverage, which was strung together by Tom Brokaw and morning show hosts Katie Couric and Matt Lauer, took twelve minutes to acknowledge the south tower had collapsed, mistaking at first that just part of the building had fallen. They had correctly reported the cities from which the hijacked airplanes had departed before they could determine the building fell.

Poor N.J. Burkett, a reporter for New York’s local ABC affiliate, was across the street from the towers when the first collapse occurred. He was filming the establishing shot so ritualistic in local news. “Take two,” he says routinely, beginning a well-practiced voiceover as the cameraman sweeps from Burkett upward to where the second plane hit, only to find the south tower ballooning out and crashing down toward them. “We better get out of the way!” he screams, crossing the transom from reporting history to participating in its devastation.

Amateurs raced to capture these moments as well, grabbing camcorders and rushing to whatever vantage point they had: a nearby apartment window, a building rooftop, through chain link fences, from the FDR.

Across the river in New Jersey, someone flicks on their home video camera and is moving quickly down the sidewalk. You can hear the camera’s operator talking to someone else from the neighborhood, going back and forth about what’s happening. They’ve realized that they can walk down the street and see with their own eyes what they’d just watched on television. As the camera reaches the corner, and as the group turns and catches a glimpse of the carnage, they cry out in disbelief. The skyline, as normal to them as the sun in the sky, has been devastated.

Throughout the gruesomely staged terror, it seemed everyone uttered the same, urgent plea: oh my God. Or, New Yorkers being New Yorkers, holy shit.

United we stood.

I visited Ground Zero three months later, on a cold December day between Christmas and New Year’s. The fires had only recently been put out, but there were still abundant signs of the nightmare from September. I remember seeing window blinds stuck in the canopy of a tree. The streets were eerily quiet, the normal bustling noise of the city that never sleeps muted out of respect.

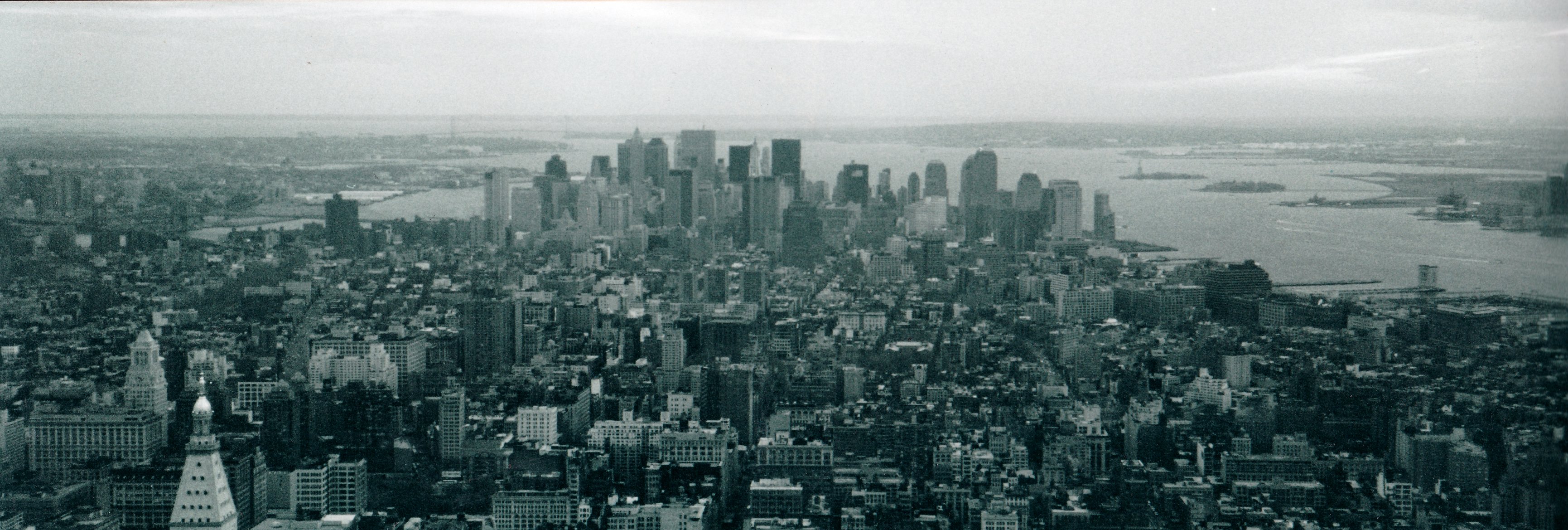

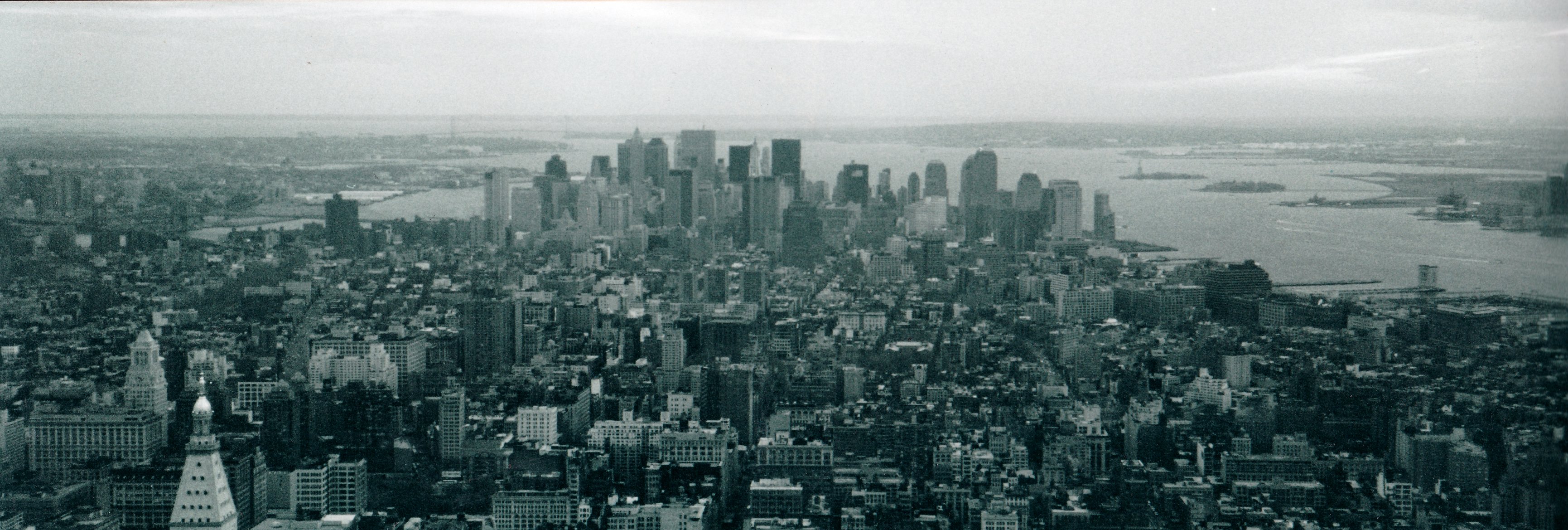

We were fortunate. We didn’t know anyone who had died, but we knew of close calls. Monmouth County, New Jersey, where I was born and an hour’s train ride from the city, lost more residents on 9/11 than any other county. I remembered rocketing to the top of the towers as a kid, visiting the observation deck and staring out in awe at the view from 110 stories up. My grandfather once had an office in the towers.

Walking around Ground Zero that December, it was difficult to reconcile what we had watched on television with the strange, bleak canvas presented before us. It did not seem possible. If our country had woken up with a sense of innocence that Tuesday morning, by day’s end we collectively tended a deep wound, and by December, its sting had become a throbbing ache.

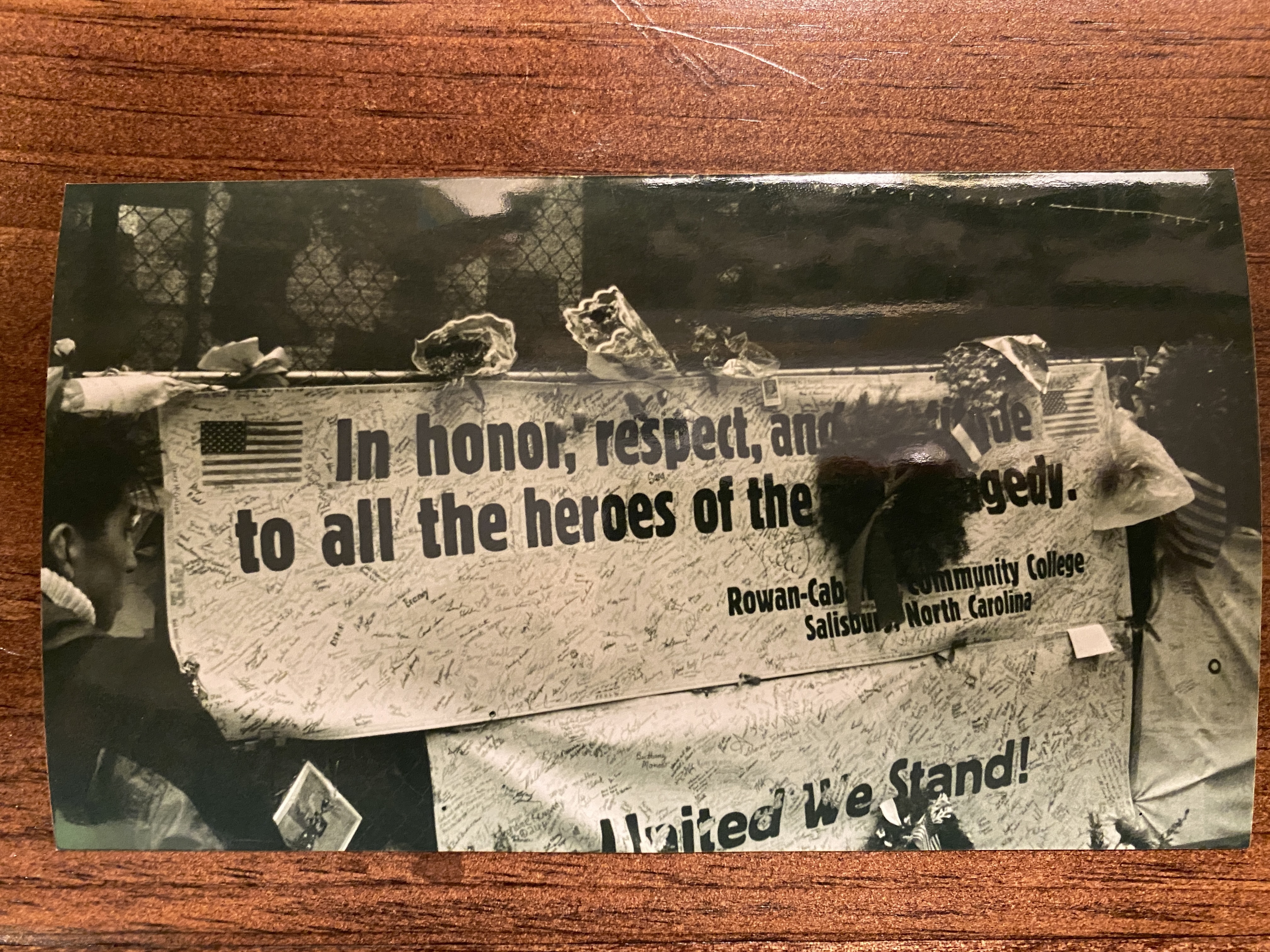

Americans had shown up for one another in ways that I had never seen before. We walked the blocks around The Pile, as firefighters called the towers’ ruins, staring at hundreds of signs, posters, and banners attached to perimeter. We saw a canvas banner bearing hundreds of signatures sent from a community college near where we lived. “In honor, respect, and gratitude to all the heroes of the 9/11 tragedy,” it read.

I remembered signing a similar such banner back at my college, though we never found it. It was one of several occasions where, hundreds of miles away, my classmates and I had gathered to talk about what had happened and what it meant. The evening of September 11th, I felt compelled to drive out and buy an American flag, which I hung in my upstairs dormitory window.

Such patriotism wasn’t an unfamiliar impulse. American flags soon sprouted everywhere–pinned to highway overpasses, covering t-shirts, roped to the backs of fire engines nationwide. Across Liberty Street from Ground Zero, workers clad the heavily damaged Deutsche Bank building in thick curtains designed to prevent pieces of it from falling to the street and injuring workers below. At the top, visible even from the Empire State Building: a large American flag.

Anyone wearing a police or fire department uniform became an instant celebrity as they traversed Manhattan. That October, dozens of musicians, actors, and dignitaries staged a benefit concert for them that ran nearly five hours long and was filled with rock and roll catharsis.

My own mother-in-law volunteered to spend a week in the city with the Southern Baptist Association’s Disaster Relief Team, where she helped clean apartments that had been inundated with dust and debris from the collapse. She wore a hazmat suit and a respirator.

In Pennsylvania, where precious little was left to recover after the heroic passengers of Flight 93 fought back against hijackers, workers recovered Todd Beamer’s watch. His phrase, “Let’s roll,” recorded just as he ended a final phone call from the Boeing 757 aimed toward the nation’s capital, became a call sign for heroism.

At the Pentagon, the government quickly went to work clearing the site and plotting a course for retribution.

That same December, David Brooks wrote in The Atlantic that the country was unified in its reaction to the terrorist attacks. More than 80 percent of Americans supported a military response to 9/11, and more than 60 percent of us were ready to accept the grave casualties our armed forces would undoubtedly suffer conducting such a response.

There was very little partisanship to our initial grieving. Although the majority of Americans weren’t directly connected to the attacks, all of us could feel its punch. Thousands of normal Americans going about their normal lives on September 11th were murdered by terrorists. If it could happen to them, it could happen to any of us.

Of course, it didn’t take too long for that unity to fracture. We waded into war–slowly at first, then all at once. Boys and girls who had watched the towers fall in their high school classrooms grew up to graduate and enlist and train and deploy to the dusty, ochre deserts and mountains of the Middle East. Bit by bit, we began a new tally of the dead: seven soldiers by the end of 2001, 30 by the end of the next, then more than 500 as war spilled into Iraq in 2003, and thousands more as the years grew long.

By then, Democrats blamed President Bush for leading the military response astray, and Republicans blamed Democrats for being unpatriotic. Culture wars caught flame, and social media whipped them into their own inferno, and Steve Jobs beamed it all to the little aluminum and glass miracles in our palms, and we all became distracted, unaware of anything else that might have been happening, even two decades of fighting and losing men and women in Afghanistan. And now….

Well, let’s not dwell on the now just yet.

Regenesis

Do you remember when David Copperfield made the Statue of Liberty disappear on television? It was a phenomenal trick, but it happened in 1983, and I was too young to make any memory of its airing. He performed the illusion, he said, to exemplify how easily liberty could be lost.

The setup wasn’t terribly complicated. Copperfield hosted his nighttime audience and its cameras on a platform before Lady Liberty, and then he dramatically raised a curtain to obscure it while meditating (or whatever he was doing) to make the statue vanish while dramatic music played over loudspeakers. After half a minute or so, the curtain dropped, and sure enough, only an empty pedestal remained.

A few years ago, Copperfield’s trick was explained. While the curtain was raised, the platform slowly rotated a few degrees. Whatever noise it might have made was drowned out by the loud music. Just before the curtain dropped, the lights on the statue were turned off, and new lights illuminated a fake pedestal built for the occasion.

It’s easy to think the twin towers simply vanished on September 11th. That morning, they were there, casting shadows across lower Manhattan in the glow of the sunrise. By evening, the thick curtain of smoke and dust dropped, and the sky was empty. New York City’s Gibraltar was disappeared.

The towers were disassembled and cascaded to the ground, however, not merely hidden off to the side. The devastating work of managing through the pile was only beginning, work that would take months of sorting through hell-hot rubble and was immaculately detailed in William Langweische’s book, American Ground: Unbuilding the World Trade Center.

It was slow work, but it was productive. Even as late as December and January, whole corpses were found buried in hidden pockets. Thousands of other items, from slippers given to first class passengers on American Airlines Flight 11, to firemen’s helmets, to wallets, were recovered and returned to family members or preserved for history.

Eventually, the compacted craters of the buildings were dug clean. The pulverized remnants were barged up the river to Fresh Kills landfill, where the debris were laid to rest among a hundred fifty million tons of common, household garbage. Much of the steel was recycled or repurposed. Contractors used crushed concrete aggregate to fill potholes and pave streets. The towers were given back to the earth.

The planning and reconstruction work at Ground Zero would consume years of time and energy. No action at the World Trade Center was without controversy–one group fiercely argued to leave the site undeveloped as a memorial while another demanded the twin towers be rebuilt just as they were, but taller. Eventually, a new tower slowly emerged from the deep bathtub dug out at the bottom of Manhattan, growing to 1,776 feet in height and opening thirteen years after the attacks.

This past summer, I brought our family there. We took the subway downtown from Central Park to the Oculus, Santiago Calatrava’s $4 billion transit station sprouting from the corner of the World Trade Center complex. We strolled underground through bright, airy walkways to the base of the new One World Trade, and I dipped my credit card into a glass and steel machine and traded a couple hundred dollars for the chance to once again ride to the top of the world.

At the observation deck, I watched as our children leaned into the windows, their eyes big as they took in the Statue of Liberty (still there, Copperfield!), the Brooklyn Bridge, and the Empire State Building. Below us, people on the street wandered about like ants, dodging toy cars and delivery trucks. I could not help peering southwest, across the river, to Newark Airport, where little silver tubes with wings floated down to land.

Later, we walked the memorial plaza and paused by each of the waterfalls that mark the footprints of the twin towers. The trees there, now a decade old, have grown in, but the names carved into the sides of the memorial still look crisp and fresh. I watched Julia run her hands along the damp sides, her fingers tracing over letters that added up to thousands of lives.

And I compulsively, briefly wept. The twin towers of the World Trade Center stood over lower Manhattan for the first 20 years and 21 days of my life. Very soon, in a few weeks, I will pass a point in time when I have lived longer without the twin towers in my life than with them. As a newly minted 40 year-old, the tragedy of 9/11 is now half a lifetime ago.

To echo Peter Jennings so many years ago, what do we have here?

That is life.

In the last few weeks I’ve spent time reading books, listening to podcasts, and watching documentaries about September 11th. It is an easy topic to consume you, and I’ve indulged it from time to time in my own writing here over the last two decades.

The best piece I’ve read about September 11th wasn’t published until this summer. Jennifer Senior tells the story of her friend Bobby McIlvaine, a man not quite seven years older than me who had the bad luck of having a meeting in the twin towers on that fateful morning. Two days before he died, he’d asked his girlfriend’s father’s blessing to propose to her. Somewhere in between the 102 minutes from the first plane’s impact to the last tower falling, Bobby’s family and friends saw their lives upended. The future bent sharply away.

His father grieved so deeply he became unmoored, doggedly pursuing conspiracy theories about the attacks. His mother hid her grief, afraid of becoming an object of pity. His girlfriend moved on with her life, married someone else.

His brother, Jeff, agonized over how in the passing years he was losing memories of Bobby–what he sounded like, how he carried himself, how he smelled. He’d trade everything for the chance to go back in time, he said, when those memories were sharper, even if they were more painful.

“It’s the damnedest thing,” Senior writes. “The dead abandon you; then, with the passage of time, you abandon the dead.”

So it is. With the COVID-19 pandemic raging, our local community college scaled back plans to commemorate the 20th anniversary of 9/11. We didn’t want to, but we felt we had to. When I was talking with the college’s president about it, we wondered how many of our students hadn’t been born when it happened, wondered how many more anniversaries until there wouldn’t be anyone left to mourn.

Bobby McIlvaine, it turns out, had a philosophical streak in him. In the days after he died, his parents found notebooks and diaries on his apartment desk filled with his writing and thinking. One passage, penned 22 days before the attacks, caught everyone by surprise:

There are people that need me. And that, in itself, is life. There are people I do not know yet that need me. That is life.

This wisdom is simple yet profound. After I read it, I came back to it, and turned it over in my head. I printed it out and taped it to my office door. In so many ways, I began to see its refrain as a battle hymn for our weary republic.

While it’s not always clear to me that the world has recovered, that things have gotten better since 9/11, what is wholly crystalized in my brain is that there are people who need me. Who need us. That in and of itself is a galvanizing force to keep moving forward.

God forbid our lives are visited again by such a tragedy as September 11th, but in truth, the odds are quite likely that we’ll all live to see another generational hallmark of similar scale. Things will fall in our lives that we had never imagined would fall. We will suck in our breath and exhale: oh my God.

There is always a future, though. There are people that need me and people I do not know yet that need me.

That is life.

Leave a Reply