When lighthouses go dark.

In the early dark of December, I recall walking down to St. David’s in Cullowhee. I was a college student, a junior I think, and it was Advent. My friend Brittany had been invited to read a meditation she’d composed, and we were both going.

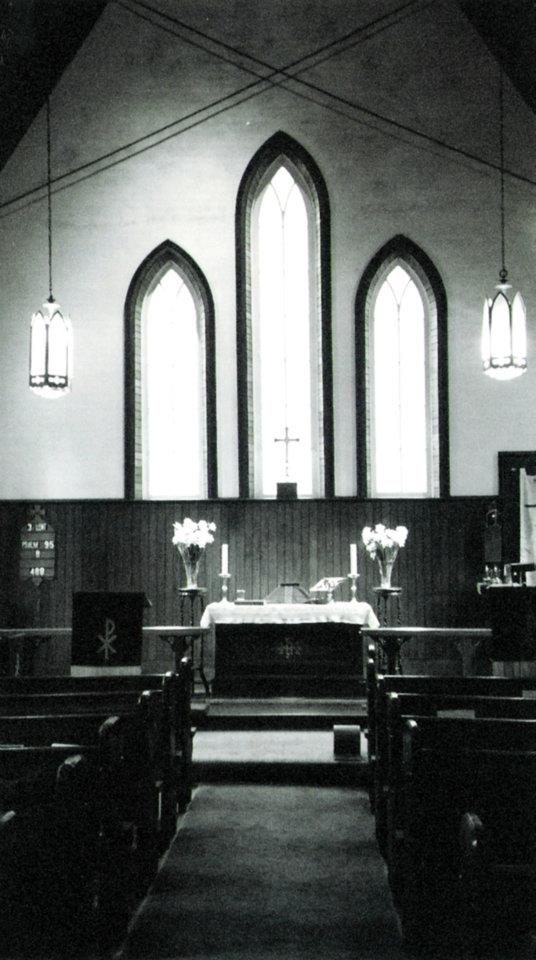

These meditations were a weekly occurrence at St. David’s. We arrived in the cold, entering into the nave directly from the red door at the side. Inside was a narrow room with a vaulted ceiling. The Advent evening prayer services were candlelit; there was a podium in the aisle for reading. A chest organ at the back provided some music. Dr. Lillian Pearson–Kelly’s piano professor–usually supplied.

I cannot remember the subject of Brittany’s meditation. I can only guess it was something literary. (We were English majors.) But the reason I was there in the first place had more to do with the rector who led the parish.

Michael Hudson was rather informal for a priest. He often delivered his homilies while pacing up and down between the pews. In the small church, his sudden proximity heightened his earnest delivery. He would rock back and forth sometimes while talking. Underneath his priest’s robes, he was often in blue jeans and hiking boots. Michael’s devotion to hiking, to being out of doors, showed up in his sermons. God was God of nature, and nature tempered his creation quite readily, so it made sense to spend time and thoughts considering what God might tell us through our environmental medium.

I knew Michael because his wife Barbara had hired me at the university’s writing center, where I worked as a tutor. Barbara was a dear mentor. At some point early on I surely shared my beginnings in the Catholic church. It wasn’t surprising that she would encourage me to come to St. David’s. Several of the English faculty were members. I hadn’t been to mass in a long time, but the first Sunday at St. David’s felt like riding a bike, the language, the motions, the framework immediately familiar. After the service, there was always a simple lunch with wine in the little house next door. It felt sophisticated. Grown-up. A proper, intelligent exploration of faith, surrounded by professors, as one might expect to be at a little university parish, but led by this wiry fellow Michael with a toothy grin and a quick wit and a deep trove of stories.

It’s hard to properly summarize it all. Barbara was a mentor, but also a counselor and guide for my early life. She listened to me (I cannot imagine how much I talked and talked) and helped me realize a few important lessons. She gave me deeply important and critical advice. As a young person, I was intent on playing a grown-up as convincingly as I could. I wanted to be taken seriously, to have my shit together. Barbara helped me understand that real life–good life–is messy, and there’s nothing to do about it. This wisdom is easy enough to capture in a paragraph, but the profundity it represents expands beyond the mountains and valleys it took to learn it and then earn the courage to share it.

I credit Michael for bringing me into the Episcopal church, a move that forever altered the arc of my spiritual life. Its scaffolds and formalities and order were all deeply appealing–although there is some irony to that, given Michael’s willingness to bend rules when necessary. He was writing hymn texts when I was a student. I remember finding printouts of them at the writing center, where Barbara would pencil comments on them and help workshop the trickier parts. His idea was to set new words to hymns from the standard Episcopal hymnal for the entire cycle, an audacious task. Eventually they were all gathered into a book and published.

Now for a brief summation of the 19 years between when I graduated college and when I returned to Cullowhee.

We would come back to visit over time, staying a weekend when we could afford it, and always stopping by St. David’s on Sundays when we did. The familiar faces changed quickly, as congregations often do for itinerant worshippers. One summer, my college roommate Austin and I helped move a piano to their house. Another time, Barbara and Michael came to the house we had on Pebblestone. We sat in the back yard near the gurgling koi pond. Every year we’d send a Christmas card and usually receive one in return. I would send writing I’d been working on, and Barbara would sometimes print them out and send them back with her own notes. Then came the period of our lives when things were hard and difficult, and things became hard and difficult for Barbara and Michael. I heard about them, not from them; they were separated, then they were divorced. In the Great Recession, the university eliminated or consolidated a number of positions, including Barbara’s. I heard she went out West.

Then, one day, it seemed all of the knots in their lives were untied. Maybe not immediately, or neatly, or perfectly straightened, but still. They were both back, and they were together. They remarried, Michael and Barbara Jane. I saw them on Facebook, photos of them hiking around. Michael wrote a blog. We exchanged emails here and there. Kelly and I had started a family by then, and Barbara seemed smitten with the children. Michael retired. I learned somewhere along the way that he’d been diagnosed with some version of dementia. He began to lose names, even when he knew faces. Speaking was difficult, but writing wasn’t. They continued to walk and hike as often as they could. Sometimes Barbara would post little updates here and there. The Covid pandemic happened. Still, most days there were tiny dispatches of life from them, photos of the beautifully normal things about them, and often a sentence or two.

About this time three years ago, somewhere around the first Sunday of Advent, we brought our children to Cullowhee to show them what would become their new home. We met our realtor at the house we were under contract to buy, and we meandered around campus, and we took in the Christmas scene in Dillsboro. We had a little time at the end of the afternoon, and we found our way over to the greenway trail near our new house. We’d only been walking a little ways when we ran into Barbara and Michael. They had aged–a lot–and there was a moment where I was worried they didn’t recognize us, but soon they did, and even though Michael couldn’t tell us much, in his eyes, I could see he knew who we were. It felt like a good omen to see them, a sign that we were moving back to a place that would take good care of us.

I still believe that is true, that this is a place where there are good people who care a lot about us, but we never saw Barbara or Michael again. A few months later, Barbara fell ill. ALS. That summer, she died.

Last month, I was back at St. David’s for Michael’s funeral, the first time I’d been there since Barbara’s funeral two years before. The service, like a Robert Frost poem, was lovely, dark and deep. Heartfelt. Like Michael. At the end of the funeral mass, we sang a hymn (all of the hymns were Michael’s settings) and walked out of the little church and up the hill to commit his ashes into the ground next to the spot where Barbara’s rested. Their daughter, Ruth–who I can remember as a child played in the tree outside the writing center after school–carried her infant daughter, Jane, named for her grandmother, and I was weepy thinking about the beautiful circle of life. The line of mourners each took a shovel of earth, gently tucking Michael into the ground he so loved.

I came home that afternoon and took out the Wagoneer for a drive, attending to all of the feelings inside. I can tell you the decision to come back to our little college town has provided us plenty of surreal moments where we transpose our radically grown-up lives on top of our youthful memories. There is no dodging the spine-tingle when I see our daughter walk the path down the hill through the rhododendron where I walked a hundred times on my way to class. It is one thing to stand in a room and consider its history, another to feel the weight of our own decades’. These are the kinds of thoughts, the sorts of essays, I would send along to Barbara for her feedback. Always.

And here we are in the middle of our lives, in a boat in the dark sea, neither shore quite in sight.

Advent, our friend and pastor Blake reminded us this morning, always begins in exile. The prophets knew plenty about it, and it wasn’t pretty, but Advent is a season of hope. Hope is a valuable thing to learn about. Hope will not put us to shame.

At home, I fixed the candles of our homemade advent wreath, and at supper we lit the first one, and we gave thanks, and I thought back to the candlelit service so many years ago at St. David’s. It felt far away.

It’s worth mourning a good life, or two good, messy lives, but layered on top is knowing the lighthouses in my life are going dark, one by one. Beloved mentors and friends joining the communion of saints. That is how it goes. Real life–good life–is not without sadness.

Amen.

ginger gregg

excellent.