An extraordinary day, and a simple act of decency.

We are standing in a dark room where photography of any kind is prohibited. Before us, in a light and climate controlled room, is the original garrison flag raised over Fort McHenry in September of 1814 following a long night of British bombardment. In the early morning light, the sight of the flag inspired Francis Scott Key to compose words that eventually became The Star Spangled Banner.

Thomas and I are standing, a bit speechless, looking at its faded colors, its clearly hand-sewn composition, its tattered edges. In the years after the War of 1812, the flag was owned by a family, who scissored off snippets of fabric to give to war heroes and friends. It was eventually given to the Smithsonian in 1907, where we are viewing it. And of course, now we all sing about the flag. This flag. I think about how singing a song with others brings us together.

Minutes later, I pause to take a seat on a wooden bench while Thomas checks out another gallery of our nation’s artifacts. I’m nursing a fractured foot, and our day started early this morning as we hiked around the Library of Congress, the Supreme Court, and the U.S. Capitol Building. The day before we’d hoofed it more than 10 miles. My orthopedic boot was not the most comfortable footwear. As I sat, I glanced at my phone and saw I had a LinkedIn message, and for whatever reason I opened it, read it, and came to a startling conclusion.

I was missing my wallet.

The impetus of our Memorial Day weekend trip was Thomas’s desire to visit the National Air and Space Museum, part of the long collection of Smithsonian Museums scattered along the National Mall. It was our first stop when we arrived early Saturday morning, and within two hours of stepping off a plane at Reagan airport, we were staring down the Wright brothers’ flyer.

“That’s the actual flyer!” I told Thomas, whose eyes grew wide as he took in the thin pieces of wood and beige canvas that together formed the symbol that’s been on license plates in North Carolina for decades. It was one of many “that’s the actual thing!” moments on our trip; the first arriving when Thomas spotted the Washington Monument from the airport.

Not long after, we were looking at the actual Apollo 11 command module and the space suit Neil Armstrong wore when he walked on the moon. There are actual airplanes hanging from the ceiling, practically in every room. The nose of a 747 sticks out from one wall. Thomas rushes up the stairs and over, so that he can view the cockpit, where a million lighted switches blanket every surface.

Around every corner, there are names and faces, a veritable highlight reel of record book feats: Armstrong, Wright, Yeager, Knievel, Cessna, and on and on. An entire display on space and satellites. Combining it all: a swatch of fabric from the original Wright flyer that had been taken to the surface of the moon and then returned to earth–to its new home at the Smithsonian.

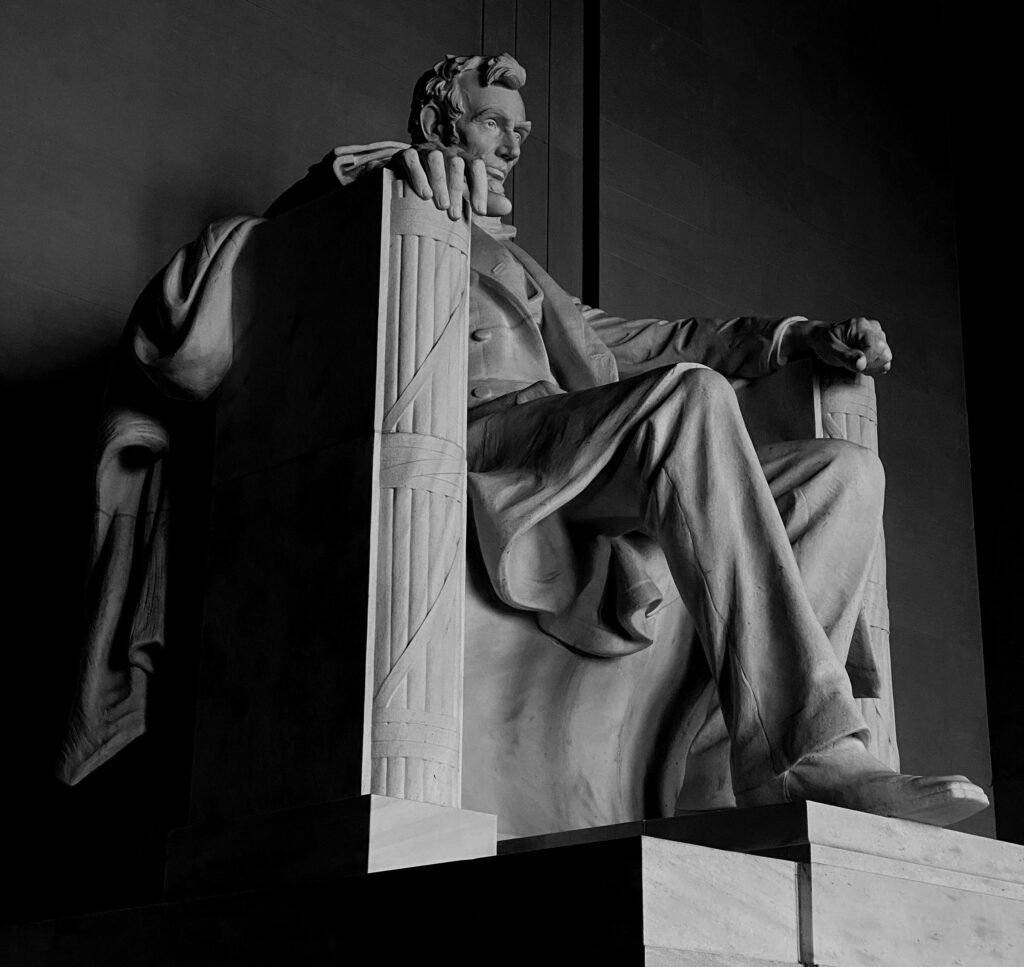

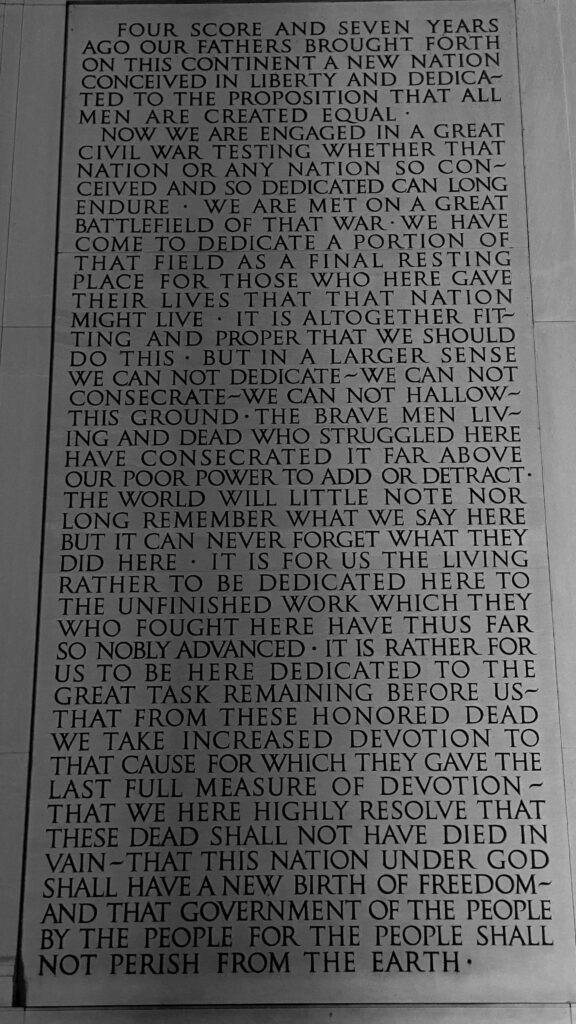

After a couple of hours of gawking, Thomas and I emerged into the bright afternoon sun. After supper, we walked to the Lincoln Memorial. We read the Gettysburg Address, engraved into the marble southern wall. We here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain.

We paused on the way down to find the spot where Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered the “I Have a Dream” speech, then walked across to see the monument dedicated to King’s memory. Later: the Korean War monument, the D.C. war memorial, the World War II memorial.

The nation’s capital is a forest of monuments, memorials, and museums, themselves populated with groves of displays, plaques, and inscriptions. There are tens of thousands of names etched, inscribed, engraved. Millions of lives that others commend us to remember: the first, the last, the totality.

The LinkedIn message is from a woman named Rubina: “Hi there! We were sitting next to each other in front of the museum and you left your wallet!”

In the Museum of American History, my heart began to race. Thomas and I are only here for the weekend, and we are due back to the airport the following afternoon. My wallet contained my identification, credit cards, hotel key. I cannot believe that I have lost it, but sure enough, my pocket is empty. My stomach tenses up when I realize the message came more than an hour and a half ago.

Quickly, I replied, thanking Rubina and sending her my phone number. I clicked on her profile photo and recognize her. Earlier, in front of the Museum of Natural History, Thomas and I had stopped for a bite to eat at the National Park Service concessions stand. It was a warm day in Washington, and only a handful of picnic tables next to the stand were shaded. Thomas and I had grabbed one, but there was still plenty of room. The woman and another man with her approached and asked if they could share the table with us. Of course, we said, and finished our meal.

We walked away, and somehow my wallet stayed behind. I stared at the LinkedIn messenger, willing a reply to come through. I notice her profile doesn’t list her last name.

I found Thomas, and together we walked back to the Natural History building. The entire time, I was kept refreshing the app. I asked the security officers inside if someone had turned in a wallet. No luck. The same at the concessions stand.

I am at a loss, unsure what to do. I lean against one of the massive columns inside the Natural History museum, an enormous elephant before me in its rotunda. I frantically begin googling Rubina, using clues from her LinkedIn page, piecing together anything I can. Miraculously, I find a phone number, but in truth, I have no idea if I even have the right person, let alone the right phone number.

“Call her, Dad!” Thomas urges. I texted instead.

Minutes pass with no reply. I take a breath, and call the number. I have to plug my opposite ear against the noise of the packed museum hall.

She answers. They are back at the townhouse they’d rented for the weekend in Arlington, packing their car, about to depart for Connecticut. Rubina can text me the address. They will wait for us if we can get there. We bolt outside.

My iPhone has offloaded my rideshare apps, and in a mad scramble, Thomas and are walking across the mall toward a side street where we can meet a ride while I stare helplessly as the app downloads at the pace of a melting glacier. Thomas yells and points to a taxi, but I explain I cannot pay for a taxi without my wallet.

Finally–finally–the app loads, and miraculously (again), my payment information is saved in the app, and I order a car, and ten minutes later a driver picks us up, and we head toward Arlington. At this point I have been texting back and forth with Rubina, and at some point I’m sure we are all thinking that this is some kind of scam, that maybe I am some kind of unreliable person, or maybe she is lying in wait to kidnap us.

Of course this isn’t the case. When we arrive before a row of neat townhouses, Rubina and her brother are there, and within seconds I have my wallet, and I’m asking her what I can do for her, offering to pay her for her kindness, and she is saying no, no, I’m just doing the right thing. She is a doctoral student from California, and they are driving across the country to her practicum in the northeast, and they decided to stop in Washington. We chat for a few minutes, and shake hands, and shake our heads at the wonder of it all, and I thank her again and again, and then they climb into their car and leave, and Thomas and I go off in search of a Metro station.

We have a concert to catch.

Lieutenant Dan is standing about 100 feet away from Thomas and me in front of a large video screen talking about D-Day. Of course it’s really only Gary Sinise, not the character from Forrest Gump, but in the back of my mind I keep hearing Tom Hanks’ voice: “Loo-ten-aynt Da-yan! Ice cream!”

Sinise is talking about the turning point in the second World War, the epic Battle of Normandy now 80 years ago, and behind him, scenes of American GIs in landing boats play across massive screens, scenes of men wading into the water, running across the beach, huddled at the base of the cliffs or sprawled out, dead, on the sand. Behind him on the stage, the National Symphony Orchestra is playing a score that hums along in real time behind the narration and film clips, finding moments here and there to soar and crescendo.

The entire scene is surreal. Thomas and I are sitting on the West Lawn of the United States Capitol Building together with probably 20,000 or so people. The Capitol is shining behind us, lit for television by massive klieg lights suspended from a crane, and before us is an arced stage draped in red, white, and blue, where the symphony sits on risers several paces behind Lt. Dan, who is joined by Joe Mantegna.

All of the production is for the PBS National Memorial Day Concert, an annual live television event commemorating lives lost in service to our country. While we were walking around the Capitol that morning, Thomas and I came upon the workers setting everything up for the show, only then realizing the concert was that day. We arrived early in the evening to grab a good seat, and thanks to my bulky orthopedic boot, we’d been granted seats right behind the VIPs.

We had watched them arrive throughout the evening. Soldiers, veterans, brass. Gold Star mothers, families. A handful of World War II veterans, all in wheelchairs, the last of a generation. Others in wheelchairs, injured in duty, missing limbs. The lineup for the evening is star-studded: in addition to Sinise and Mantegna, Bryan Cranston, Jenna Malone, Mary McCormack, and B.D. Wong will speak. Gary LeVox, Jamey Johnson, Patina Miller, and Cynthia Erivo will perform.

It is a concert, but it also a live television event, and watching it begin is dramatic–the countdown, the public address announcer smoothly guiding the introduction, the symphony rising to the occasion, everything blocked and rehearsed and coordinated.

On cue, a line of soldiers from each branch of service form a color guard and advance to the middle of the stage area. The music shifts, and the crowd rises to its feet, and Thomas and I instinctively reach for our hats to remove them, and the countless uniformed men and women bring their hands up in a crisp salute as Ruthie Ann Miles* sings the National Anthem.

She stands on a brightly lit stage in the middle of the crowd, away from the symphony. A second conductor stands before her, directing her performance while watching a video feed of the symphony’s conductor.

There is a camera at the end of a long boom, and I see it swivel around toward the Capitol, and I turn to see a sea of American faces, the stars and stripes far away before the massive white rotunda, and I realize that just that morning we had viewed the garrison flag that inspired the song we are singing, a flag that improbably survived a merciless onslaught of British munitions. I glance down at Thomas, and close my eyes and see him in his Boy Scout uniform, the khaki shirt and olive pants not dissimilar from the uniforms around us, as he brought forth the flag at their last service, advancing the colors through a Methodist church basement in quiet Appalachia.

There on the Capitol lawn, we bore witness to an American tapestry of ingenuity, innovation, and remembrance. We saw George Washington’s uniform and the top hat Lincoln wore the night he died. At the concert, we heard three tender narratives of sacrifice, each written by veterans and performed by the actors on stage, who finished each monologue by stepping down into the audience and embracing the original author.

And that day, we were touched ourselves by a simple example of American decency performed by someone who decided to do the right thing, even if it meant sacrificing time that could have been spent on the road to the next stop.

The concert finished with a rousing rendition of “God Bless America,” and the crowd eagerly joined, all of us standing under the breezy Sunday night sky, the grandeur of the Capitol behind us, the mall and monuments stretching before us. My boy and I and twenty thousand of us singing, our hearts full of gratitude for the land that we love, every voice a fractional example of the spirit it takes to do something extraordinary for someone else.

*Author’s note: I did not know Ruthie Ann Miles’s story before I wrote this piece–born in Arizona to a Korean mother and raised in Hawaii, she is a Tony-winning actress and singer. In 2018, she and her four year-old daughter were struck by a car that plowed into them in a crosswalk. Miles, who was also pregnant at the time, was severely injured and lost her baby. Her four year-old daughter died.

1 Pingback