EDUCATION

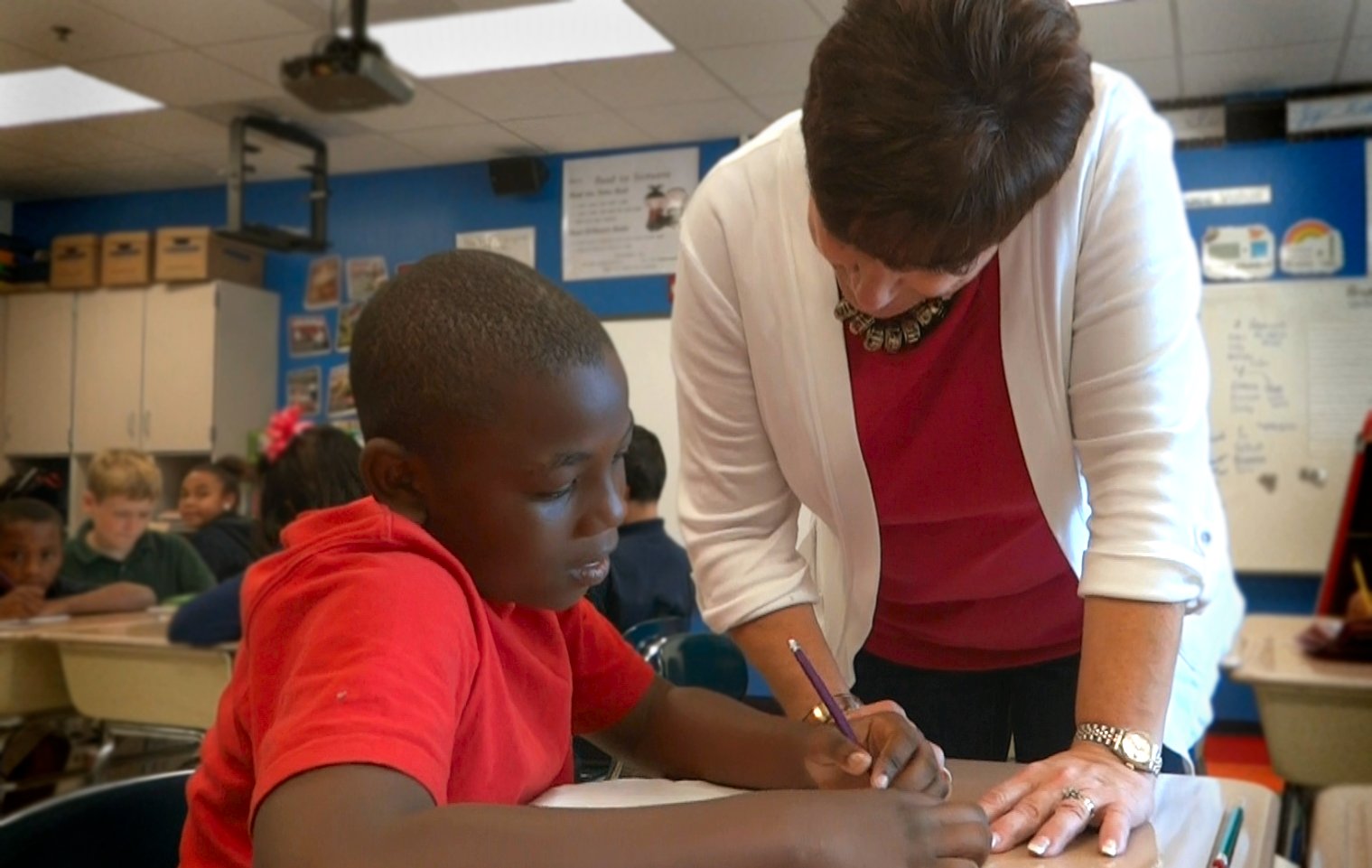

Letter grades can’t possibly tell the whole story of a school. An inside look at the passionate work of a school our state says is a letter away from failing.

(Author’s note: this story was originally published in September 2015.)

A few weeks ago, my wife began her fifteenth year teaching elementary school music. She’s been in the same classroom and the same school for her entire career, and she’s seen thousands of kids come through her hallway.

She enjoys her job; she teaches every kid in the building, so she’s kind of like a local celebrity. We rarely can make it through the grocery store (or anywhere around town) without someone running up to her, hugging her leg, and running off with a smile. It’s a happy thing to see.

This week, though, her school received a North Carolina school performance grade of D.

This is the second year that the state has assigned school performance grades. Like the grades you received when you were a student, they range from A-F. I’ve written before how grading systems like these don’t tell the whole story, especially since they tend to invite enormous criticism.

There’s also evidence that supports that school performance grades are simply barometers for poverty in schools; indeed, my wife’s school is one of those schools where most of the kids are on free or reduced lunch. More than 70 percent, actually.

Her students have it rough. Many of them don’t get to sleep on beds. Their bikes are regularly stolen. Their fathers aren’t always around. Whenever my wife invites students to share what they did over the weekend at the beginning of class, she often hears stories about parents or siblings who were arrested. Or shot.

Several years ago, I stopped by my wife’s classroom to drop something off with her that she’d forgotten. After I left, one of her students raised his hand and asked who the man was who’d just visited their classroom.

“He’s my husband,” she replied. “Mr. Hogan.”

“Do he beat you?” the student asked.

Do he beat you? It was an honest question, asked in earnest by a kid who’d seen plenty of domestic violence in his life. And that question said a lot about the baggage this particular student–and so many of his peers–brings to class every day.

Part of the reason that my wife’s school earned a D grade is because the ratings are based 80 percent on student achievement and 20 percent on growth. Grade-level math and reading tests make up the student achievement numbers, and there are some difficult results in there. I won’t point out the raw numbers, but in several cases fewer than half of the students were proficient in math in the grade levels tested.

So my wife’s school earned a D. But you know what? The school exceeded growth.

Students there notched 87 percent growth. That means that last school year, the students at my wife’s school outperformed the expectations for academic growth that the state set for them based on previous data. In other words, even though half of the kids weren’t yet to the bar on math or reading, they’d still learned more math than the state thought they would.

Which means the teachers at my wife’s school are working hard and achieving results with their students.

This year, my wife’s principal has created a school-wide theme called “Operation Possible.” The idea is that, beginning on Day 1, students are pushed to consider what comes at the end of their education. What jobs would they like to work? Where might they want to live? What are their dreams?

The entire faculty has embraced the concept. Several of them are coming to school dressed like doctors and nurses (operation possible, get it?), ready to diagnose students’ passions and enable them to follow them.

One of the administrators runs a leadership program that identifies students on the brink who could use extra one-on-one mentoring. They’re called ambassadors, and they form an exclusive club. The school provides them with collared shirts and ties (there’s a female group starting this year), and they lead visitors on tours, work with younger students, and learn from career professionals about making good choices in life.

The ambassador program has demonstrated great success, keeping kids out of trouble, and reaping the reward of what an investment in a troubled young person’s life can produce.

Other faculty have shown enormous initiative over the summer. One noticed her students’ extra energy distracted them from learning, so she wrote a grant and earned funding to buy standing desks, stability ball chairs, and other furniture that allowed students to work out their kinetic buildups and still stay focused.

Another teacher, whose students attend classes in a mobile unit (did I mention my wife’s school, which was expanded in the last five years, is overcrowded?), grew tired of her students getting soaked on rainy days during the walk to the main building. So, she wrote and earned a nearly $20,000 grant that will help build a covered walkway between the buildings.

These teachers have been working all summer long to prepare lessons, brainstorm best practices, and secure resources for the coming school year. They do this in spite of lower than average salary, little support among state legislators and politicians, and few if any job perks, not even duty-free lunch time.

My wife and her colleagues not only deliver everything in their being to teach their kids, but they work with three churches in our community to make sure kids have shoes on their feet and clothes on their backs. (Literally. They give away hundreds of school uniforms, socks, shoes, underwear, etc. every year.)

And even though the school provides breakfast and lunch to students, the faculty and its community partners pack bags full of food to send home with students every weekend–because sometimes there’s no food at home.

You can blame whomever you want for the problems my wife’s students face every day when they go home. Meanwhile, the teachers and staff at my wife’s school are giving it everything they’ve got to succeed in spite of those limitations. They are fearless, driven by the passion of serving our future, by the hope that every one of these kids might have a chance–a better chance–because of the work they’re doing there.

Today, my wife woke up at 5 a.m. to get ready for work. Dozens of her colleagues did the same thing–sacrificing sleep to make sure they’re prepared for the challenges and opportunities that will walk through the door today.

There are hundreds of schools like my wife’s out there: places where a letter grade can’t possibly tell the whole story of the mission going on inside. So the next time you see a school with a D on its report card, remember there’s a hive full of passionate teachers in that building, humming along together in harmony, doing all they can to help their kids.

This article was originally published here on September 3, 2015. Since then, it has been referenced and quoted in a piece by The Progressive Pulse.

Leave a Reply